Germany stutters

The general election in Germany produced a sharp swing to the right. The two main parties of the centre-right and centre-left, the Christian Democrats/Social Union (CDU-CSU) and the Social Democrats (SPD) suffered significant losses in their share of the vote. The party of Chancellor Angela Merkel lost 8.5% pts from the 2013 election to finish with 33%; and the SPD lost 5.2% pts to finish with 20.5% – both achieving the lowest share of the vote since 1945. The share of the vote going to the two main parties, which were in a ‘grand coalition’, is hardly above 50% of those voting – and the voter turnout rose to 75% from 71% in 2013.

The big gainer was the anti-immigrant, ultra-nationalist, anti-muslim, Alternative for Germany (AfD) which polled 12.6%, compared with 4.7% in 2013 and entered the German parliament (Bundestag) for the first time. The other major gainer was the petty-bourgeois, neo-liberal Free Democrats (FDP) which polled 10.7% compared to 4.8% last time and re-entered the Bundestag. Die Linke (Left) party polled more or less the same as last time with 9.2% and so did the Greens with 8.9%. Indeed, the left (if you include the Greens in that) polled less than 40% of the total vote, even lower than in 2013.

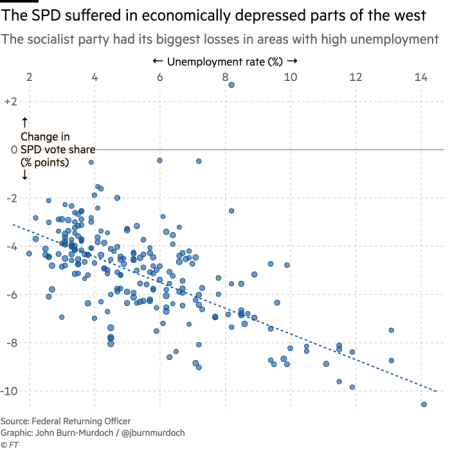

The SPD says that they will not enter a new grand coalition with the CDU, and that’s not surprising after the hammering they have taken in the election for being part of Merkel’s government. The SPD particularly lost support in higher unemployment areas of West Germany, revealing that the poorest sections of the working class do not see the SPD as fighting for them any longer.

The big gains by the AfD made it Germany’s third-largest party in the Bundestag. The phenomena of ‘populist’ right-wing nationalist parties that we have seen in France (National Front), the UK (UKIP), Italy (La Liga) and Greece (Golden Dawn) demonstrate the fragmentation of the political status quo in Europe in this Long Depression. Some (not all) of the poorest and least organised of the working class, along with small business and self-employed, have turned to nationalism for an answer. They think that the causes of their demise are immigrants, handouts to other EU countries and big business – in that order.

Germans are used to immigrants. Germany is the second most popular migration destination in the world, after the US. Over one out of five Germans has at least partial roots outside of the country, or about 18.6m. But the question of immigration became a huge issue in Germany because of the disaster of the Middle East and the massive and fast influx of refugees, around 2m in the last two years into Germany. Most of these refugees were placed in the poorest parts of east Germany, already under the pressure of poorer housing, education and social services.

It is an economic issue because of the previous policies of the SPD and CDU in introducing so-called labour ‘reforms’ that created a whole layer of part-time temporary employees for German business on very low wages. This is what Marx called a ‘reserve army of labour’. This kept labour costs down for German industry and laid the basis for the sharp rise in the profitability of German capital from the early 2000s up to the global financial crash.

About one quarter of the German workforce now receive a “low income” wage, using a common definition of one that is less than two-thirds of the median, which is a higher proportion than all 17 European countries, except Lithuania. A recent Institute for Employment Research (IAB) study found wage inequality in Germany has increased since the 1990s, particularly at the bottom end of the income spectrum. The number of temporary workers in Germany has almost trebled over the past 10 years to about 822,000, according to the Federal Employment Agency.

So the reduced share of unemployed in the German workforce was achieved at the expense of the real incomes of those in work. Fear of low benefits if you became unemployed, along with the threat of moving businesses abroad into the rest of the Eurozone or Eastern Europe, combined to force German workers to accept very low wage increases while German capitalists reaped big profit expansion. German real wages fell during the Eurozone era and are now below the level of 1999, while German real GDP per capita has risen nearly 30%.

Continuarea aici