Săptămîna aceasta grupul “Chto Delat?” este invitatul nostru special. CriticAtac vă invită vineri 26 octombrie, ora 19.30, în strada Dianei 4, la evenimentul: Artă şi Politică în Rusia / Art and Politics in Russia. Detalii aici.

Sfârşitul anilor 1990 în Europa de Est şi Rusia au pus punct unei decade haotice, concluzia patetică a unei epoci de dezamagiri şi colaps. Prinşi în vortex-ul restructurării democratic-capitaliste care, contrar retoricii oficiale, a păstrat inegalităţi dramatice între clasa muncitoare şi minoritatea bogată, câţiva artişti au început să răspundă crizelor social-culturale. Intervenţiile lor au înbinat întrebări legate de supravieţuire, rezistenţă şi reconstrucţie, în faţa eşecurilor materiale ale socialismului şi a renovaţiei neoliberale, caracterizate de alienare şi degradare, înfiltrându-se din ce în ce mai mult sub vopseaua proaspătă a proto-capitalismului.

Aşa este şi cazul colectivului artistic “Chto Delat?”, care activează în St. Petersburg şi Moscova, lucrând la intersecţia dintre artă, filozofie şi activism politic. Numele ales de artişti se traduce “Ce e de facut?,” titlul faimosului roman al lui Nikolay Cernyshevsky, care propunea o agendă de reformă radicală la mijlocul secolului XIX în Imperiul Rus. Titlul a fost preluat şi de Lenin într-unul dintre faimoasele sale pamflete revoluţionare publicate în 1902. La secole distanţă, “Ce e de facut?” funcţionează ca un mnemonic pentru organizarea de sine a proletariatului prin angajament politic.

Aşa este şi cazul colectivului artistic “Chto Delat?”, care activează în St. Petersburg şi Moscova, lucrând la intersecţia dintre artă, filozofie şi activism politic. Numele ales de artişti se traduce “Ce e de facut?,” titlul faimosului roman al lui Nikolay Cernyshevsky, care propunea o agendă de reformă radicală la mijlocul secolului XIX în Imperiul Rus. Titlul a fost preluat şi de Lenin într-unul dintre faimoasele sale pamflete revoluţionare publicate în 1902. La secole distanţă, “Ce e de facut?” funcţionează ca un mnemonic pentru organizarea de sine a proletariatului prin angajament politic.

Infiinţat în 2003 de un grup de artişti, filozofi, cercetători sociali şi activişti originari din St. Petersburg, Moscova si Nizhny Novgorod, colectivul utilizează practici ce nu se încadrează într-o definiţie simplă. Concret, platforma lor produce ziare şi opere de artă – de la video, piese de teatru radiofonice şi la spectacole – iniţiind intervenţii artistice în domenii culturale şi medii instituţionale atât pe plan local cât şi pe plan internaţional. Ziarele şi lucrările video ale colectivului sunt distribuite gratis în cadrul expoziţiilor, demonstraţiilor, conferinţelor şi sunt de asemenea disponibile on-line, pe site-ul platformei Chto Delat?: http://www.chtodelat.org. Lucrările lor politice şi polemice sunt bazate pe principiile de lucru ale avant-gardei ruseşti, în special tradiţia constructivistă şi a sovietelor – o formă importantă de organizare iniţiată în timpul Revoluţiei Ruseşti din 1917.

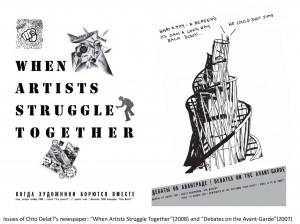

“Chto Delat?” declară cu tărie afiliarea lor la acţiune politică, gândire critică şi la concretizarea inovaţiei artistice, concentrându-se pe probleme urgente din societatea rusă contemporană şi eforturi paralele în contextul internaţional. Aşa cum Dimitry Vilensky şi David Riff, doi membri fondatori, subliniază în ziarul intitulat “Când Artiştii Luptă Împreună” din noiembrie 2008, strategia colectivului este de a traduce si a materializa teorii de stânga, articulate în producţia artistică realizată în condiţii post-comuniste. Parte integrală a acestei metode de lucru este ceea ce Vilensky numeşte “actualizarea” proiectelor emancipative radicale ale avant-gardei, uitându-se înapoi spre momente cheie din patrimonial cultural al Rusiei, când proiectele politice şi cele estetice erau indivizibile.[1]

“Chto Delat?” declară cu tărie afiliarea lor la acţiune politică, gândire critică şi la concretizarea inovaţiei artistice, concentrându-se pe probleme urgente din societatea rusă contemporană şi eforturi paralele în contextul internaţional. Aşa cum Dimitry Vilensky şi David Riff, doi membri fondatori, subliniază în ziarul intitulat “Când Artiştii Luptă Împreună” din noiembrie 2008, strategia colectivului este de a traduce si a materializa teorii de stânga, articulate în producţia artistică realizată în condiţii post-comuniste. Parte integrală a acestei metode de lucru este ceea ce Vilensky numeşte “actualizarea” proiectelor emancipative radicale ale avant-gardei, uitându-se înapoi spre momente cheie din patrimonial cultural al Rusiei, când proiectele politice şi cele estetice erau indivizibile.[1]

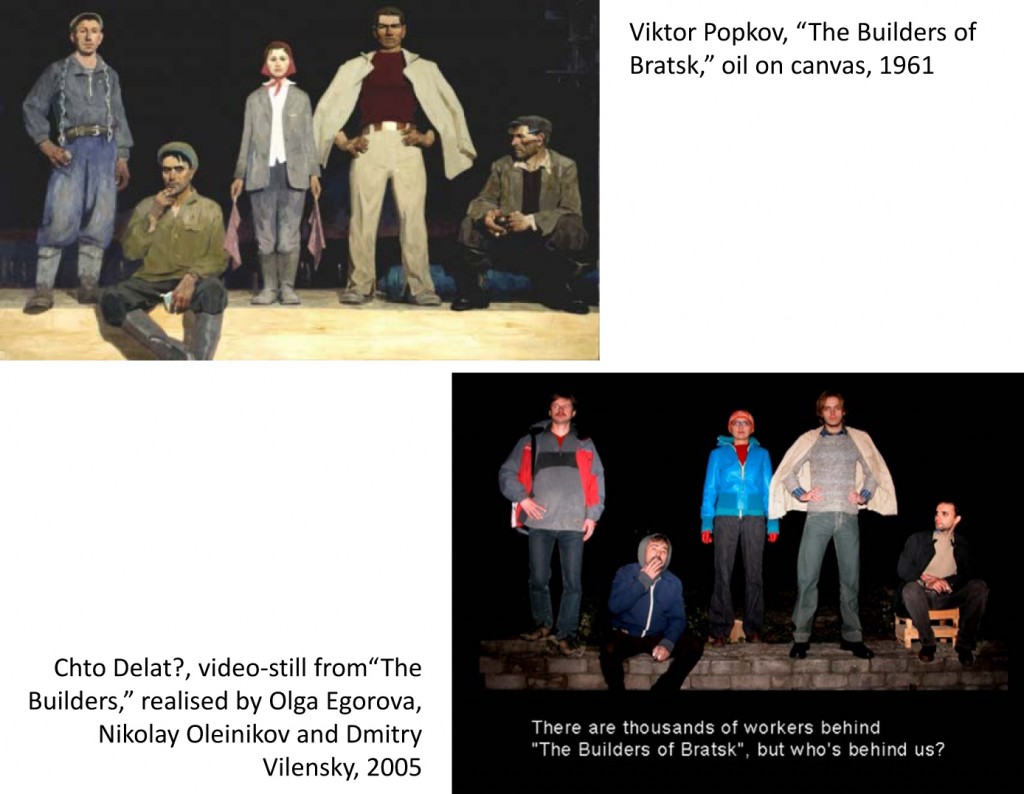

În lucrarea din 2005, “Muncitorii,”[2] colectivul a transferat în mediul video unul dintre cele mai importante tablouri ale artistului rus Viktor Popkov, “Muncitorii din Bratsk” (1961). Lucrarea lui Popkov prezintă cinci lucrători, patru bărbaţi şi o femeie, meditând asupra condiţiilor de muncă şi cum acestea ar putea afecta transformarea societăţii socialiste. În schimb, video-ul devine animat de prezenţa fizică a membrilor “Chto Delat?,” angajaţi într-un dialog reflexiv despre dinamica producţiei muncii lor artistice. Urmând semnificaţiile tabloului din timpul în care a fost realizat, cu convingerea că nu poate exista progres în cultură decât prin schimburi şi asimilări de experienţe, artiştii aduc imaginea proletariatului de odiniară în sistemul de referinţă al audienţei contemporane. Prin interogarea propriei lor poziţii şi activităţi în societate, colectivul deschide imaginaţia audienţei spre a construi exerciţii de reflecţie similare. In “Muncitorii,” compoziţia originală este îngheţată în timp, spre deosebire de organizarea platformei “Chto Delat?” care pendulează între coeziune şi mişcări pe direcţii diferite, proiectând imaginea unei cooperative culturale care conectează subiectivităţi individuale cu transformări în realitatea socială.

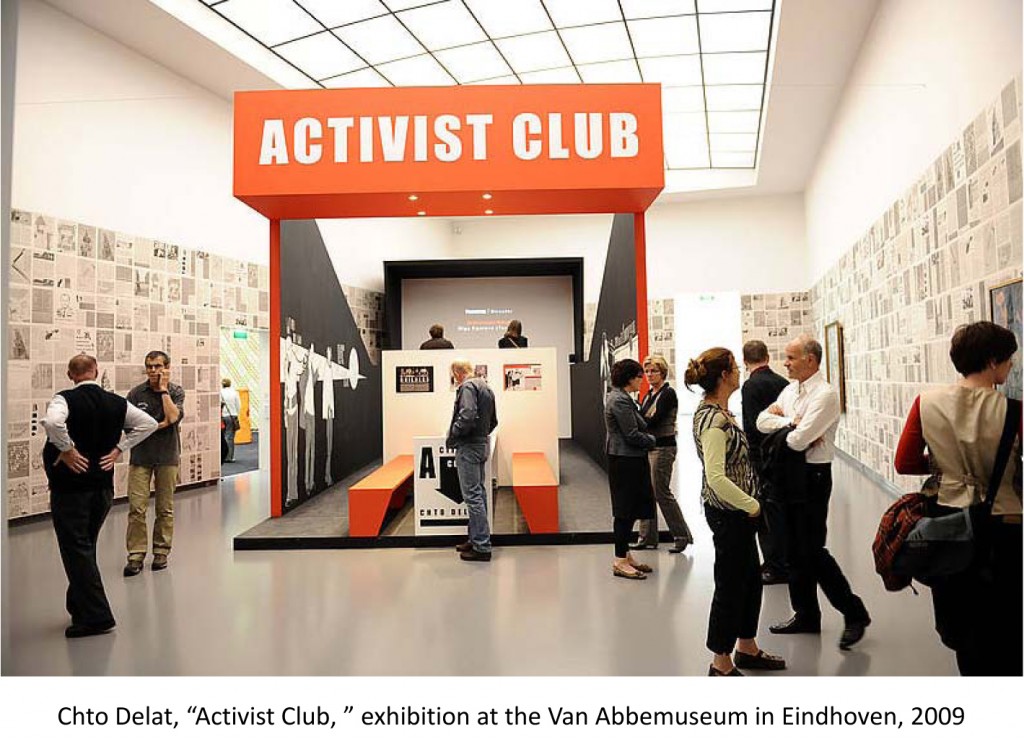

Intervenţiile instituţionale ale artiştilor pot fi descrise prin metafora unui proces prismatic, în cadrul căruia teme sociale şi culturale sunt descompuse şi aduse din nou împreună prin baza comună a platformei. În această privinţă, o instalaţie importanta “Chto Delat?” a fost realizată la Van Abbemuseum din Eindhoven, în 2009, cu ocazia căreia artişti au reactivat proiectul artistului constructivist Alexander Rodchenko din 1925- “Clubul Muncitorilor.” Produs pentru Expoziţia Internaţională de Arte Decorative şi Industriale Moderne din Paris, lucrarea originală a lui Rodchenko a reprezentat la vremea respectiva un model de organizare a proletariatului din fostul USSR: re-formulând timpul liber ca o activitate colectivă dinamică, îndreptată spre educaţie, producţia cunoaşterii şi participarea activă în viaţa politică.

Intervenţiile instituţionale ale artiştilor pot fi descrise prin metafora unui proces prismatic, în cadrul căruia teme sociale şi culturale sunt descompuse şi aduse din nou împreună prin baza comună a platformei. În această privinţă, o instalaţie importanta “Chto Delat?” a fost realizată la Van Abbemuseum din Eindhoven, în 2009, cu ocazia căreia artişti au reactivat proiectul artistului constructivist Alexander Rodchenko din 1925- “Clubul Muncitorilor.” Produs pentru Expoziţia Internaţională de Arte Decorative şi Industriale Moderne din Paris, lucrarea originală a lui Rodchenko a reprezentat la vremea respectiva un model de organizare a proletariatului din fostul USSR: re-formulând timpul liber ca o activitate colectivă dinamică, îndreptată spre educaţie, producţia cunoaşterii şi participarea activă în viaţa politică.

In schimb, “Chto Delat?” au creat un spaţiu cinematografic cu o zonă de studio şi dezbatere – un Club al Activiştilor – folosindu-se de spaţiul public al muzeului, pentru a iniţia un forum de discuţie despre poziţia artei în societate. Mai mult, colectivul a produs şi a distribuit o ediţie relaţionată a ziarului lor inititulată: “Care Este Scopul Artei?”[3] Prin această provocare retorică, analizată prin dezbateri, analize critice şi intervenţii vizuale pe parcursul a aproximativ o duzină de pagini, ei subliniază fără echivoc că baza activităţilor lor sunt proiectele avant-gardei îndrepate asupra transformării radicale a societăţii prin re-imaginarea relaţiilor inter-personale, prin gândire marxistă. Declarând că arta contemporană ar trebui să fie de partea claselor neprivilegiate, artiştii concep funcţia artei ca fiind elaborarea instrumentelor cunoaşterii, pentru a discerne totalitatea contradicţiilor care guvernează domeniul social al economiei şi politicii.

Trei dintre lucrările video ale colectivului au fost proiectate în Clubul Activiştilor din Eindhoven: “Muncitorii” (2005), “Sanwhich-People Supăraţi sau Lauda Dialecticii” (2006) şi “Songspiel Perestroika”(2008). Scopul acestui articol nu este de a analiza detaliat aceste lucrări – dar vreau să le subliniez pentru că ele amintesc de o alta tradiţie avant-gardistă – Metoda lui Brecht – pe care colectivul a îmbinat-o cu actualizarea tradiţiei artistice Ruseşti angajată politic. Din acest punct de vedere “Chto Delat?” apar în dialog cu teoreticianul american Fredric Jameson care, în opera sa din 1998 “Brecht şi Metoda” a argumentat pentru relevanţa criticii politice şi sociale a lui Brecht[4] – nu într-un viitor probabil sau indecis încă, ci acum, în situaţia de după Războiul Rece, dominată de retorica capitalistă. Într-adevăr, înainte de a realiza trilogia Songspiel, colectivul l-a pus pe Brecht pe harta lor teoretică: în 2006 ei au publicat o ediţie a ziarului lor intitulată “De ce Brecht?”[5] în care au elaborat investiţia lor în a face conexiunea între gândire intelectuală şi acţiune. Astfel ei construiesc pe tradiţia brechtiană de a analiza circumstanţe istorice tangibile care pot duce la solidaritate colectivă şi re-înnoire socială în perioade istorice de cumpănă.

Forma concretă a acestor angajamente este o serie de opere video colective, “Triptica Songspiel,” dintre care “Perestroika Songspiel”[6] (2008) este prima dramă – ce conectează songspielul brechtian ca o formă de critică socială încărcată politic, cu un moment cheie din timpul restructurării fostei Uniuni Sovietice. Lucrarea se desfăşoară pe parcursul unei zile de solidaritate şi avânt – 21 August 1991, dată ce marchează victoria civică asupra loviturii de stat sovietice, când membri ai partidului communist au încercat sa-l înlăture pe fostul preşedinte Mikhail Gorbachev de la putere şi să anuleze reformele începute de acesta. Lucrarea video nu este o simplă re-memorializare a acestor evenimente istorice, ci o descompunere structurată ca şi o tragedie antică. Protagoniştii ei sunt un cor de operă – simbolizând publicul general – şi cinci personaje-tip Perestroika: democratul, businessman-ul, revoluţionarul, naţionalistul şi o feministă. Prin retorică şi dezbateri, aceşti actori îşi analizează activităţile din timpul acestor evenimente cruciale, în acelaşi timp reflectând asupra poziţiei lor în societate – legată de lupta pentru a construi o nouă direcţie politică pentru ţara lor. Bazat pe dovezi documentare şi mărturii ale acestor episoade istorice, video-ul dezvăluie atât imaturitatea politică a corpului civic cât şi iminenta sufocare a idealurilor lor. Atât corul cât şi cei cinci reprezentanţi din societate se adresează direct audienţei prin cântece, comentarii şi sloganuri politice – o strategie pe care Brecht a denumit-o “teatru dialectic” – catalizatoare pentru o re-imaginare radicală a subiectivităţilor şi relaţiilor sociale.

Forma concretă a acestor angajamente este o serie de opere video colective, “Triptica Songspiel,” dintre care “Perestroika Songspiel”[6] (2008) este prima dramă – ce conectează songspielul brechtian ca o formă de critică socială încărcată politic, cu un moment cheie din timpul restructurării fostei Uniuni Sovietice. Lucrarea se desfăşoară pe parcursul unei zile de solidaritate şi avânt – 21 August 1991, dată ce marchează victoria civică asupra loviturii de stat sovietice, când membri ai partidului communist au încercat sa-l înlăture pe fostul preşedinte Mikhail Gorbachev de la putere şi să anuleze reformele începute de acesta. Lucrarea video nu este o simplă re-memorializare a acestor evenimente istorice, ci o descompunere structurată ca şi o tragedie antică. Protagoniştii ei sunt un cor de operă – simbolizând publicul general – şi cinci personaje-tip Perestroika: democratul, businessman-ul, revoluţionarul, naţionalistul şi o feministă. Prin retorică şi dezbateri, aceşti actori îşi analizează activităţile din timpul acestor evenimente cruciale, în acelaşi timp reflectând asupra poziţiei lor în societate – legată de lupta pentru a construi o nouă direcţie politică pentru ţara lor. Bazat pe dovezi documentare şi mărturii ale acestor episoade istorice, video-ul dezvăluie atât imaturitatea politică a corpului civic cât şi iminenta sufocare a idealurilor lor. Atât corul cât şi cei cinci reprezentanţi din societate se adresează direct audienţei prin cântece, comentarii şi sloganuri politice – o strategie pe care Brecht a denumit-o “teatru dialectic” – catalizatoare pentru o re-imaginare radicală a subiectivităţilor şi relaţiilor sociale.

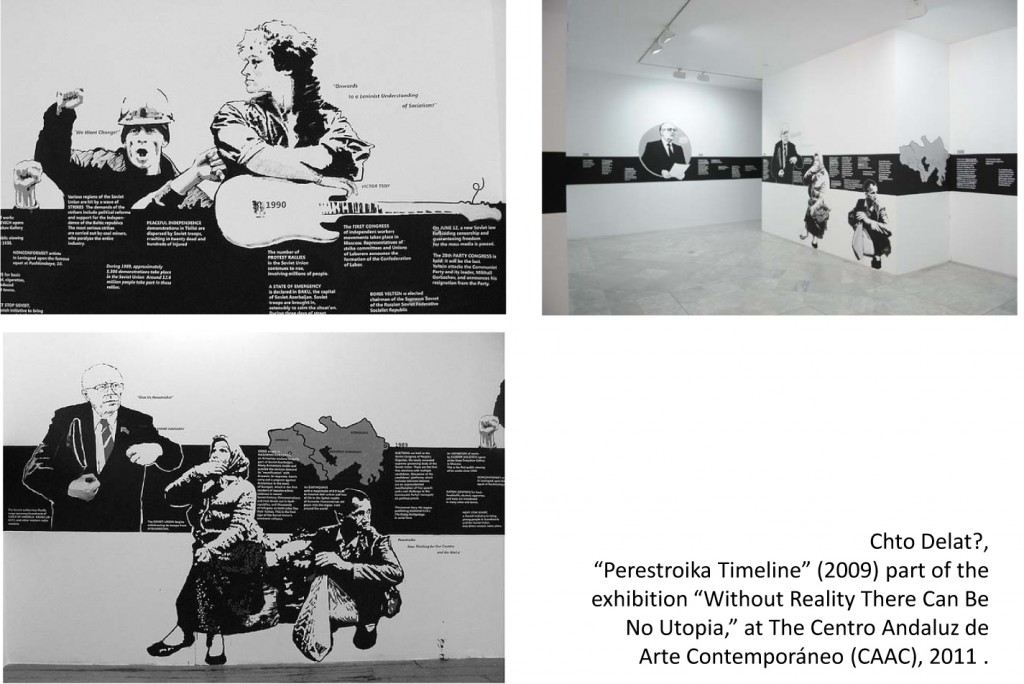

“Perestroika Songspiel” este legată în mod intim de o instalaţie recurentă a colectivului – intitulată “Cronologia Perestroikăi” – realizată la Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo din Sevilia şi la Bienala de la Istanbul, ambele în 2009. Această lucrare video şi grafică, prezentată în versiuni diferite răspunzând spaţiilor specifice, este o alta materializare a conceptului sus-menţionat de “cristalizare.” Instalaţia combină songspiel-urile colective cu materialul fotografic transferat pe pereţii expoziţiei de membrii colectivului: Nikolay Oleynikov, cu Thomas Campbell si Dmitry Vilenski – sub foma unui palimpsest de clase sociale, generaţii şi actori politici. Songspiel-ul şi Cronologia sunt instrumente artistice de re-dramatizare a Istoriei Politice: ele marchează o trecere de la înţelegerea tradiţională a arhivelor artistice sau istorice legate de Războiul Rece – care doar reprezintă evenimentele istorice. În schimb aceste instrumente ajută la crearea unui spaţiu de reflecţie şi activism în jurul relevanţei politice şi sociale ale reprezentării estetice ale acestor momente şi participanţilor la ele.

“Perestroika Songspiel” este legată în mod intim de o instalaţie recurentă a colectivului – intitulată “Cronologia Perestroikăi” – realizată la Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo din Sevilia şi la Bienala de la Istanbul, ambele în 2009. Această lucrare video şi grafică, prezentată în versiuni diferite răspunzând spaţiilor specifice, este o alta materializare a conceptului sus-menţionat de “cristalizare.” Instalaţia combină songspiel-urile colective cu materialul fotografic transferat pe pereţii expoziţiei de membrii colectivului: Nikolay Oleynikov, cu Thomas Campbell si Dmitry Vilenski – sub foma unui palimpsest de clase sociale, generaţii şi actori politici. Songspiel-ul şi Cronologia sunt instrumente artistice de re-dramatizare a Istoriei Politice: ele marchează o trecere de la înţelegerea tradiţională a arhivelor artistice sau istorice legate de Războiul Rece – care doar reprezintă evenimentele istorice. În schimb aceste instrumente ajută la crearea unui spaţiu de reflecţie şi activism în jurul relevanţei politice şi sociale ale reprezentării estetice ale acestor momente şi participanţilor la ele.

“Chto Delat?” interoghează producţia istoriei şi polticii, a reciprocităţii şi uniunii dintre aceste domenii într-o manieră nebanală. Activităţile lor de aproape un deceniu – ce îmbină poziţii artistice cu teorii Marxiste – continuă să evolueze prin adaptare şi alterare în cadrul unor diverse practici culturale, construind pe concepte nedezvoltate într-o avant-garda, într-un mediu sau context cultural. Criticii de specialitate le-au descris lucrările ca fiind nelegate, amestecând lucruri care nu sunt evident compatibile. Această critică este validă până la un punct, dar aşa cum membrul fondator Dmitry Vilenski a evidenţiat, colectivul este interesant mai presus de dezvoltarea unor metode de a rezolva contradicţii în spaţiul expoziţional, ca şi în viaţa de zi cu zi: îmbinând forma estetică avant-gardistă cu conţinutul radical, sau încercând să găsească echilibrul între spontenaitatea revoluţionară şi disciplina constructivă.

În această întreprindere artistică, colectivul este ghidat de viziunile şi teoriile avant-gardelor afiliate politic din diverse discipline, care le oferă o bază de cunoaştere ce problematizează noţiuni apatice de fomă, funcţie şi context. Activităţile lor caută să deturneze subsumarea relaţiilor inter-umane în cadrul aşa-zisei totalităţi capitaliste – prin eliberarea imaginaţiei audienţei spre situaţii care cad înafara acestei logici, şi încurajând potenţialul pentru acţiuni politice colective. Din cauza afilierii lor poltice, platform ”Chto Delat?” se află în conflict cu structurile de ordine actuale, de la scena de artă prohibitivă din Rusia, dominată de institutii puternice şi oligarhi corporatişti, până la spaţiile expoziţionale din Vest, pe care le provoacă spre acţiuni încărcate politic de observaţie şi comunicare cu publicul. Ca de exemplu, în cadrul expoziţiei “Ostalgia” deschisă la The New Museum din New York luna aceasta, când mergând împotriva conceptului de nostalgie pentru perioada de dinainte de 1989, colectivul a ales să prezinte o cronologie multi-media relevantă pentru istoria politică recentă a Statelor Unite, în legatură cu Socialismul ca şi fenomen global.

Care ar fi concluzia acestui articol? Cititorul ar putea să aleagă să ignore relevanţa acestui exemplu de colectiv artistic pentru contextul din Romania, ca fiind legat de circumstanţele particulare ale avant-gardei din Rusia şi a Stângii. Dar aş vrea să sugerez o altă variantă. Fără a anula diferenţe istorice şi de context, aş dori să propun o tangenţă în faţa unor probleme comune din sfera socială, întrepătrunse economic şi poltic. Unul dintre domeniile în care aceste urgenţe se manifestă este cultura, prin intermediul căreia proiecte educaţionale liberatoare şi de organizare sistemică pot fi catalizate şi concretizate.

Care ar fi concluzia acestui articol? Cititorul ar putea să aleagă să ignore relevanţa acestui exemplu de colectiv artistic pentru contextul din Romania, ca fiind legat de circumstanţele particulare ale avant-gardei din Rusia şi a Stângii. Dar aş vrea să sugerez o altă variantă. Fără a anula diferenţe istorice şi de context, aş dori să propun o tangenţă în faţa unor probleme comune din sfera socială, întrepătrunse economic şi poltic. Unul dintre domeniile în care aceste urgenţe se manifestă este cultura, prin intermediul căreia proiecte educaţionale liberatoare şi de organizare sistemică pot fi catalizate şi concretizate.

În Romania, limitele sunt deseori neclare între filozofia lui Marx, communism şi recent-decedatul aparat dictatorial care pretindea să fi realizat socialismul – care ar trebui condamnat în bună măsură. Mi se pare că de cele mai multe ori luptele sociale se încadrează într-un ciclu comatos, intentând proces comunismului pentru crime împotriva umanităţii – măsura politicii corecte – şi în genral ostracizând Stânga. În acelaşi timp, vedem cum curenta organizare capitalist-democratică este departe de promisiunile iniţiale, de integritate politică şi fair-play economic.

În timp ce corpul civic renunţă la acţiune politică – aceasta din urmă văzută ca şi parte integrantă a mecanismelor de corupţie (de înainte şi după 1989) – urgenţele colective ramân disociate unele de altele, iar inegalitaţile dintre muncitori şi minoritatea bogată se consolidează. Această dublă negare neutralizează posibilitatea unei rezistenţe commune, a recuperării poziţiilor politice de către muncitori şi a cunoaşterii unei lumi în afara imperativului de a consuma. Condiţii similare pot fi observate în societatea rusă contemporană, unde posibilitatea de solidarizare este testată de fragmentarea grupurilor de muncitori activi politic din diverse domeniile. Unul dintre cele mai mari obstacole pe care le înfruntă activiştii culturali este consolidarea teoriei, artei, filozofiei cu eforturile uniunilor locale şi grupurilor de ajutor reciproc. Conştienţi fiind de diferenţa dintre Teorie şi Practică, “Chto Delat?” încearcă să reducă limitele acestei diviziuni. Astfel, ei oferă un exemplu puternic de anagajament şi solidaritate culturală, care nu încetează să provoace spectatorul cultural pasiv în a gândi şi a acţiona politic.

Autoarea îi mulţumeşte lui Dmitry Vilensky pentru sfaturile şi materialele acordate pentru acest articol.

[1] Chto Delat?, When Artists Struggle Together/ Când Artiştii Luptă Împreună, St: Petersburg, Noiembrie 2008. Toate aceste texte şi publicaţii sunt accesibile online la: http://www.chtodelat.org/

[2] Videoul “Builders/ Muncitorii” poate fi vizionat online la : http://vimeo.com/6877630

[3] Ziarul “What is the use of Art?/ Care Este Scopul Artei?” poate fi downloadat de pe site-ul colectivului: http://www.chtodelat.org/

[4] Vezi Fredric Jameson, Brecht and Method (London and New York: Verso, 1998)

[5] Ziarul “Why Brecht?/ De Ce Brecht?” poate fi downloadat de pe site-ul colectivului: http://www.chtodelat.org/

[6] “Perestroika Songspiel” poate fi vizionată online: http://vimeo.com/6877630

–––––––––––––

Political Art Actions: On Chto Delat? and the Avant-Garde

When the 1990s came to a close in the Eastern part of Europe and in Russia, it was not just the end of a chaotic decade, but the contemptible conclusion of a painful era of struggles, collapse and disappointment. Caught in the vortex of democratic-capitalist re-structuring that – despite rhetorical claims to the contrary – nonetheless preserved marked inequalities between workers and the wealthy minority, few artists began responding to prescient socio-cultural crises. Their interventions embodied questions of survival, resistance and reconstruction, faced with the lasting material failures of socialism and the onslaught of neoliberal renovation marked by alienation and decay – seeping under the fresh paint of proto-capitalism.

Such is the case of Chto Delat?, a collective based in St. Petersburg and Moscow, Russia, who work at the nexus of art, philosophy, political activism and theory. The collective’s name translates to “What is to the done?,” the title of Nikolay Cernyshevsky’s mid 19th century novel that put forward an agenda of radical reform in Imperial Russia – a title which Lenin later took for one of his famous revolutionary pamphlets from 1902. Centuries apart, “What is to be done?” functions as a mnemonic for self-organization of the proletariat through political engagement.

Founded in 2003 by a group of artists, philosophers, social researchers and activists from St. Petersburg, Moscow, and Nizhny Novgorod, Chto Delat?’s practice defies straightforward categorization. Concretely, the platform produces newspapers and artworks – video, radio plays and performances – staging artistic interventions in cultural domains and institutions, both locally and internationally. The collective’s newspapers and video works are distributed free of charge at exhibitions, demonstrations, conferences and through their website: http://www.chtodelat.org. Their political and polemical works are methodologically grounded in the working principles of the Russian avant-garde – in particular the constructivist tradition – and the soviets – an instrumental form of self-management initiated during the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Chto Delat? strenuously declare their allegiance to political action, engaged thought and the concretization of artistic innovation, focusing on urgencies in Russian contemporary society and related struggles in the international context. As founding members Dmitry Vilensky and David Riff emphasized in the November 2008 issue of their newspaper – “When Artists Struggle Together,” the collective’s strategy is concerned with the materialization and translability of leftist theory – articulated in artistic practice under post-communist conditions. Part and parcel of this working method is what Vilensky coined as “the actualization” of the radical emancipatory projects of the avant-garde, looking back to key-moments in Russian cultural heritage when aesthetic and political agendas were bound together.[1]

In an earlier work, “The Builders,” (2005)[2] the collective transferred onto video one of painter Viktor Popkov’s most seminal works, “The Builders of Bratsk” (1961). The original painting portrays 5 workers, 4 men and a woman thinking about the conditions of their labor and how it may affect the transformation of society. The video in turn becomes animated by the physical presence of members from the collective in front of the camera, engaged in a self-refective dialogue about the production of their own work. Building on the interpretation of the painting at the time it was produced, and, I would add, on the wisdom that culture cannot progress except through exchanges and assimilation of experiences, Chto Delat? bring the faded exponents of the proletariat up-close to the contemporary viewer. By interrogating their own position and practice, they open the viewer’s imagination to construct similar exercises of reflection. In “Builders,” the original composition appears frozen in time, while the organization of the Chto Delat’s platform pendulates between coming together and moving across different directions – a cultural cooperative connecting private subjectivities to transmutations in social reality.

Chto Delat?’s interventions in institutional spaces can perhaps be described as a prismatic process through which themes are deconstructed and recaptured through the common denominator of the platform. Telling in this regard is Chto Delat?’s seminal installation at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven in 2009, where the collective engaged with constructivist artist Alexander Rodchenko’s 1925 project “Workers’ Club. ” Produced for the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, Rodchenko’s work was a model for the organization of the proletariat in the former USSR: reimagining leisure as a collective, dynamic activity, aimed at education, the production of knowledge and participation in political life.

In turn, Chto Delat? designed a cinema area, complete with a study and discussion space – An Activists’ Club – using the museum to initiate a discussion forum about the position of art in society. Further, the collective produced and distributed a related issue of their newspaper entitled “What is the Use of Art?.”[3] Through this rhetorical provocation – deconstructed through debates, statements and visual interventions in the space of about a dozen pages- they emphasize the grounding of their practice in avant-garde projects aimed at the radical transformation of society through the re-imagining of inter-personal relationships coming from Marxist thought. Declaring that contemporary art should be on the side of the oppressed, they conceived its function to be the elaboration of instruments of knowledge – to discern the totality of contradictions governing the social domain of the economic and the political.

Three of the collective’s video works were shown in the Activists’ Club in Eindhoven: “Builders” (2004-2005), “Angry Sandwich-people or in Praise of Dialectics” (2006) and “Perestroika Songspiel” (2008). Although I am confined by the limits of this article to enter a deeper analysis of these videos, I want to foreground them as constructing on another avant-garde tradition – the Brechtian Method – which the collective have intertwined with the actualization of the Russian heritage of politically engaged practice. In this respect Chto Delat? seems to be in dialogue with American theorist Frederic Jameson’s case for the continuing relevance of Brecht’s social and political critique, espoused in the former’s 1998 oeuvre, “Brecht and Method.”[4] Jameson argues for Brechtian contemporary relevance – not only for some undecided or merely probable future, but right now, in the post-Cold-War market-rhetorical situation. Indeed, even before producing “Perestroika Songspiel,” the collective put Brecht on their theoretical map. In 2006 they published an edition of their newspaper entitled “Why Brecht?”[5] in which they elaborated their investment in linking intellectual thought with action, by building on Brecht’s legacy of analyzing tangible historical circumstances that can lead to collective solidarity and social renewal in times of historical duress.

The concrete form of this engagement are a series of collective video works, “Songspiel Triptych,” of which “Perestroika Songspiel” (2008)[6] is the first drama – connecting the Brechtian songspiel, as a form of politically charged social critique, with a seminal moment during the restructuring of the former Soviet Union. Namely, the video focuses on a day of unprecedented uprising and solidarity – August 21, 1991 the civil victory over the Soviet Coup D’État, when Communist Party hard-liners attempted to remove then president Mikhail Gorbachev from power and overturn the latter’s reforms. The work is not merely a re-memorialization of those historical events but a deconstruction structured along the lines of a an ancient tragedy. Its protagonists are an operatic chorus – the embodiment of the general public and five Petestroika- types: the democrat, the businessman, the revolutionary, the nationalist and the feminist. Through rhetoric and debate, the actors analyze their actions during these seminal events, reflecting on their position in society and their struggle to forge a new political path for their country. Based on documentary evidence and witness testimonies of these historical episodes, the video reveals both the political immaturity of the civic body and the subsequent suffocation of their visions. The choir as well as the five societal representatives directly address the viewer through songs, commentaries and political slogans – a strategy that Brecht coined as “dialectical theater” – catalyzing the ground for a radical re-imagining of subjectivities and social relations.

“Perestroika Songspiel” is closely related to a recurring installation “Perestroika Timeline,” materialized at The Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo in Seville and the Istanbul Biennale in 2009. This graphic and video work, presented in different versions responding to specific spaces, is another instantiation of the afore-mentioned concept of “crystallization.” It merges the collective songspiels with photographic material transferred onto the exhibition walls by collective members Nikolay Oleynikov, with Thomas Campbell and Dmitry Vilenski – as a palimpsest of classes, generations and political actors. The Songspiel and the Timeline are artistic tools to re-stage political history : they mark a shift in the traditional understanding of Cold War artistic or historical archives that merely present on historical events – to engendering a space for reflection and activism around the social and political relevance of aesthetic representation of those moments and actors.

Chto Delat?’s interrogation of the production of both history and politics, their unity and reciprocity is not banal. Their years-long venture of fusing cultural positions with Marxist theory continues to evolve through adaptation and alteration amongst cultural practices, looking to concepts left undeveloped in one avant-garde, medium or cultural context. Critics have oftentimes described their works as uneven, mixing things together that are not readily compatible. This is to some extent valid, but as founding member Dmitry Vilenski emphasizes the collective is concerned with developing methods to solve contradictions in real life: interweaving avant-garde form with radical content or finding the balance between revolutionary spontaneity and constructive discipline.

As such, they are guided by the visions of politically affiliated avant-gardes from different disciplines to provide a framework for rediscovery that challenges apathetic notions of form, function and context. Their practice seeks to displace the subsumption of human relations to the so-called totality of capitalism – by freeing spaces in the viewer’s imagination for situations that fall outside this logic, and enabling him/her to seize the potential for collective political action. As a result, Chto Delat?’s practice is in conflict with the given order, may that be the prohibitive art scene in their native Russia, dominated by powerful institutions and corporate power-players, or even the Western institutional spaces which they challenge into politically charged acts of observation and communication with audiences. For example, on the occasion of the exhibition “Ostalgia,” which opened at the New Museum in New York this month, the collective chose to go against the concept of nostalgia for the period before 1989, and presented a multi-media chronology that analyzes the recent political history of the United States in relation with Socialism as a global movement.

What is the conclusion of this article? One may choose to dismiss this relevancy of this example for the context in Romania, as bound with the particular circumstances of the Russian avant-garde tradition and the Left. But I would like to suggest otherwise. Without reducing historically distinct but related contexts, I would like to propose that we allow for tangents in the face of common challenges relegated to the social sphere, embedded in the economic and political. One of the orders on which these struggles are manifest is culture, through which projects of liberating education and systematic organization can be catalyzed into concretization.

In Romania, the lines are oftentimes blurred between the philosophy of Marx, communism, and the recently deposed dictatorial apparatus of socialist pretense that should be rightly condemned. Over and over again, the struggles revolve in a comatose cycle, putting communism on trial for crimes against humanity as a politically correct measure, and generally ostracizing the left. At the same time, no one can deny that the current capitalist-democratic order is far-falling from the promises of political probity and economic equity it set out to achieve.

As the civic body renounces political action – seen as already imbricated into the mechanisms of corruption (before and after 1989) – it can only further the dissociation of social struggles from each other, supporting the consolidation of inequalities between workers and a wealthy minority . This double bind neutralizes the possibility for a common resistance, of the reclaiming of political positions by workers and of the awareness of a world beyond imperative consumption. Similar conditions can be observed in contemporary Russian society, where the possibility for solidarity is tested by the fragmentation of groups of politically active workers from different domains. One of the biggest challenges engaged cultural activists face is the consolidation of theory, art, philosophy with the efforts of local unions and mutual aid groups. Recognizing the difficult space between Theory and Practice, Chto Delat? carry on pushing the limits of this divide. As such, they provide a powerful example of engagement and solidarity channeled through culture that continues to challenge the adequately sensitive, passive cultural spectator into thinking and acting politically.

The author would like to thank Dmitry Vilenski for providing advice and materials for this article.

[1] Chto Delat?, When Artists Struggle Together, St: Petersburg, November 2008. All newspapers and texts are accessible online at: http://www.chtodelat.org/

[2] “The Builders” can be viewed online here: http://vimeo.com/6878627

[3] The newspaper issue “What is the use of Art?” can be downloaded from the collective’s website: http://www.chtodelat.org/

[4] See Fredric Jameson, Brecht and Method (London and New York: Verso, 1998)

[5] The newspaper issue “Why Brecht?” can be downloaded from the collective’s website: http://www.chtodelat.org/

[6] “Perestroika Songspiel” can be viewed online: http://vimeo.com/6877630